Abstract

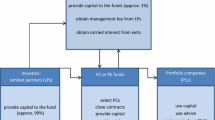

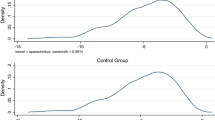

This paper investigates the differences in the return generating process of venture capital (VC)-backed firms and their peers that operate without VC financing. Using a unique hand-picked database of 990 VC-backed Belgian firms and a complete population of Belgian small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), we focus on the extent to which the presence of a VC investor affects the sensitivity of a firm’s returns to the changes in the capital structure, in the operating cycle, and in the industry dynamics. The differences may stem from the (self-) selection of better companies into VC portfolios, from the venture capitalists’ (VCs) value-adding activities, and/or from both. We examine these factors in the context of a complex simulation procedure which allows separating selection from value-adding when traditional approaches are difficult to implement. Our results indicate that VC-backed firms are able to extract more rent from the changing industry conditions and from the optimizations in their capital structure. The presence of VCs in the firm’s equity seems to have only a marginal effect on the operating cycle efficiency. Overall, the results are suggestive of the value-adding being the main driver of the VC-backed firm’s performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Scholars have also documented that prospective entrepreneurial firms may self-select themselves into better VCs (Hsu 2004).

The term “first-round financing” is equivalent to the terms “initial capital injection”, “initial investment”, etc.

In this sense, VC financing serves as a viable alternative to the bank capital.

Even if the efficiency is not an objective per se, we may expect that VCs’ involvement still benefits the operating process via the cost-reductions and value enhancements.

It is worth noting that this list is all we have as an initial input. Unfortunately, we do not possess any information on the investor or the deal itself, e.g., the valuation, the number of subsequent financing rounds, the investor type, the syndication, etc.

The coverage of Belgian VC deals in these databases is far from complete.

All companies in Belgium, regardless their listing status or size, are obliged to file complete financial statements with the National Bank of Belgium. Bureau Van Dijk next compiles these into the commercially available BELFIRST electronic database.

For start-ups, we took the corresponding values in the injection year.

If a portfolio firm belongs to the first or the last decile of its industry, only the following or preceding decile, respectively, is taken.

All random integers here are generated from the uniform distributions.

\(R_{3_{i}}\) depends on the size of the PG corresponding to \(R_{2_{i}}.\)

The sectors are aggregated using the first three digits of the NACE-BEL code. This ensures consistency with MS-PG matching procedure, which is also based on the three-digit correspondence.

Some companies in the sample show zero values of AGE and EMPL. AGE is 0 if a company is VC-backed from inception; we force NA initial value for the AGE in such cases. EMPL may take the value of 0 when the company does not employ staff in the legal sense, e.g., contract workers with the status “independent”. We add 1 to the EMPL variable to force the existence of logs.

We checked for the partial correlations with lags (Ljung–Box Q stat) as well as for the presence of the unit roots (Im, Pesaran and Shin W stat, ADF Fisher χ2, PP Fisher χ2) in all series. Data and tests are available upon request.

The first loading (β i ) represents the cross-section fixed effect constant, followed by the common factor betas, which are assumed to be constant over time and cross-sections. The term \(u_{i,t}\) should be considered as an independent variable in Eq. (3), since its value is determined earlier in Eqs. (1) and (2).

For convenience, we use terms “simulated mean”, “simulated average”, “mean of the simulated distribution”, and “average of the simulated distribution” interchangeably.

For example, the median regression is a particular case of the quantile regression when the dependent variable is the conditional median.

For instance, if we are interested in the effect of the VA_TA, E_TA, and \(\Updelta({\rm LOGIND})\) on the performance of the most performing firms, we specify and estimate the parameters for the 0.9th quantile over the complete sample, and not over the firms in this quantile only.

The estimates of the simulated distributions for control variables are available upon request.

References

Alperovych, Y., & Hübner, G. (2011). Explaining returns on venture capital backed companies: Evidence from Belgium. Research in International Business and Finance, 25(3), 277–295.

Baeyens, K., & Manigart, S. (2003). Dynamic financing strategies: The role of venture capital. The Journal of Private Equity, 7(1), 50–58.

Baum, J. A., & Silverman, B. S. (2004). Picking winners or building them? Alliance, intellectual, and human capital as selection criteria in venture financing and performance of biotechnology startups. Journal of Business Venturing 19, 411–436.

Bottazzi, L., da Rin, M., & Hellmann, T. (2008a). Who are the active investors? Evidence from venture capital. Journal of Financial Economics, 89, 488–512.

Bottazzi, G., Secchi, A., & Tamagni, F. (2008b). Productivity, profitability and financial performance. Industrial and Corporate Change, 17(4), 711–751.

Chanine, S., Filatotchev, I., & Wright, M. (2007). Venture capitalists, business angels, and performance of entrepreneurial IPOs in the UK and France. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 34(3/4), 505–528.

Cochrane, J. H. (2005). The risk and return of venture capital. Journal of Financial Economics, 75, 3–52.

Cornelli, F., & Yosha, O. (2003). Stage financing and the role of convertible securities. Review of Economic Studies, 70, 1–32.

Cumming, D. J. (2005). Capital structure in venture finance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 11, 550–585.

de Bettignies, J.-E. (2008). Financing the entrepreneurial venture. Management Science, 54(1), 151–166.

de Clercq D., & Manigart, S. (2007). The venture capital post-investment phase: Opening the black box of involvement. In: Handbook of research on venture capital, Chap. 7 (pp. 193–218). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Inc.

Dimov, D. P., & Shepherd, D. A. (2005). Human capital theory and venture capital firms: Exploring “home runs” and “strike outs”. Journal of Business Venturing, 20, 1–21.

EVCA (1998–2007). EVCA yearbooks 1998–2007. New York: European Private Equity and Venture Capital Association.

Gompers, P. (1995). Optimal investment, monitoring, and the staging of venture capital. Journal of Finance, 50, 1461–1490.

Gompers, P., & Lerner, J. (2001). The venture capital revolution. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(2), 145–168.

Gorman, M., & Sahlman, W. A. (1989). What do venture capitalists do?. Journal of Business Venturing, 4(4), 231–248.

Hand, J. R. (2007). Determinants of the round-to-round returns to pre-IPO venture capital investments in U.S. biotechnology companies. Journal of Business Venturing, 22, 1–28.

Harris, M., & Raviv, A. (1991). The theory of capital structure. Journal of Finance, 46(1), 297–355.

Heckman, J. J. (1976). The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection and limited dependent variables and a simple estimator for such models in “Annals of Economic and Social Measurement” (Vol. 5, pp. 120–137). Cambridge, MA: NBER.

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Hellmann, T. (1998). The allocation of control rights in venture capital contracts. RAND Journal of Economics, 29(1), 57–76.

Hellmann, T. (2006). IPOs, acquisitions, and the use of convertible securities in venture capital. Journal of Financial Economics, 81, 649–679.

Hellmann, T., & Puri, M. (2000). The interaction between product market and financing strategy: The role of venture capital. Review of Financial Studies, 13(4), 959–984.

Hellmann, T., & Puri, M. (2002). Venture capital and the professionalization of start-up firms: Empirical evidence. Journal of Finance, 57(1), 169–197.

Hochberg, Y. V., Ljungqvist, A., & Lu, Y. (2007). Whom you know matters: Venture capital networks and investment performance. Journal of Finance, 62(1), 251–301.

Hsu, D. H. (2004). What do entrepreneurs pay for venture capital affiliation? Journal of Finance, 59(4), 1805–1844.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and evolution of the industry. Econometrica, 50(3), 649–670.

Kaplan, S. N., & Schoar, A. (2005). Private equity performance: Returns, persistence, and capital flows. Journal of Finance, 60(4), 1791–1822.

Kaplan, S. N., & Strömberg, P. (2003). Financial contracting theory meets the real world: And empirical analysis of venture capital contracts. Review of Economic Studies, 70, 281–315.

Klepper S. (1997) Industry life cycles. Industrial and Corporate Change, 6(1), 145–181.

Klepper, S., & Simons, K. L. (2005). Industry shakeouts and technological change. Journal of Industrial Organization, 23, 23–43.

Knockaert, M., Lockett, A., Clarysse, B., & Wright, M. (2006). Do human capital and fund characteristics drive follow-up behaviour of early stage high-tech VCs? International Journal of Technology Management, 34(½), 7–27.

Koenker, R., & Basset, G. (1978). Regression quantiles. Econometrica, 46(1), 33–50.

Korteweg, A., & Sørensen, M. (2010). Risk and return characteristics of venture capital-backed entrepreneurial companies. Review of Financial Studies, 23(10), 3738–3772.

Kortum, S., & Lerner, J. (2000). Assessing the contribution of venture capital to innovation.RAND Journal of Economics, 31(4), 674–692.

Landajo, M., Andrès, J., & Lorca, P. (2008). Measuring firm performance by using linear and non-parametric quantile regressions. Applied Statistics, 57(2), 227–250.

Lerner, J. (1999). The government as venture capitalist: The long-run impact of the SBIR program. Journal of Business, 72(3), 285–318.

López-Gracia, J., & Sogorb-Mira, F. (2009). Testing trade-off and pecking order theories financing SMEs. Small Business Economics, 31, 117–136.

Macmillan, I. C., Kulow, D. M., & Khoylian, R. (1989). Venture capitalists’ involvement in their investments: Extent and performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 4(1), 27–47.

Macmillan, I. C., Siegel, R., & Subbanarasimha, P. N. (1985). Criteria used by venture capitalists to evaluate new venture proposals. Journal of Business Venturing, 1(1), 119–128.

Macmillan, I. C., Zemann, L., & Subbanarasimha, P. (1987). Criteria distinguishing successful from unsuccessful ventures in the venture screening process. Journal of Business Venturing, 2(2), 123–137.

Manigart, S., Baeyens, K., & Hyfte, W. V. (2002). The survival of venture capital backed companies. Venture Capital,4(2), 103–124.

Megginson, W. L., & Weiss, K. A. (1991). Venture capitalist certification in initial public offerings. Journal of Finance, 46(3), 879–903.

Ooghe, H., Laere, E. V., & Langhe, T. D. (2006). Are acquisitions worthwhile? An empirical study of the post-acquisitions performance of privately held Belgian companies. Small Business Economics, 27, 223–243.

Ooghe, H., & Wymeersch, C. V. (2006). Traité d’Analyse Financière. Antwerp: Intersentia.

Sapienza, H. J. (1992). When do venture capitalists add value? Journal of Business Venturing, 7(1), 9–27.

Sapienza, H. J., Amason, A. C., & Manigart, S. (1994). The level and nature of venture capitalist involvement in their portfolio companies. Managerial Finance, 20(1), 3–17.

Serrasqueiro, Z., Nunes, P. M., Leitão, J., & da Rocha Armada, M. J. (2009). Are there non-linearities between SME growth and their determinants? A quantile approach. Working paper, European Financial Management Association (EFMA) 2009 Annual Meeting.

Sørensen, M. (2007). How smart is smart money? A two-sided matching model of venture capital. Journal of Finance, 62(6), 2725–2762.

Trigeorgis, L. (1999). Real options. London: The MIT Press.

Tyebjee, T. T., & Bruno, A. V. (1984). A model of venture capitalist investment activity. Management Science, 30(9), 1051–1066.

Vanacker, T. R., & Manigart, S. (2010). Pecking order and debt capacity considerations for high-growth companies seeking financing. Small Business Economics, 35, 53–69.

Wright, M., & Robbie, K. (1998). Venture capital and private equity: A review and synthesis. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 25(5/6), 521–570.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Belgian Fund for Fundamental Scientific Research (Fonds de la Recherche Fondamentale Collective, FRFC). We are grateful to Sophie Manigart, Mike Wright, Bernard Surlemont, Pierre-Armand Michel, Michael Ghilissen, and anonymous referees for their useful comments and remarks on earlier versions of this paper. Georges Hübner thanks Deloitte Luxembourg for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alperovych, Y., Hübner, G. Incremental impact of venture capital financing. Small Bus Econ 41, 651–666 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9448-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9448-6