Abstract

This paper studies how frictions to foreign bank operations affect the sectoral composition of banks’ foreign positions, their funding sources, and international bank flows. It presents a parsimonious model of banking across borders, which is matched to bank-level data and used to quantify cross-border frictions. The counterfactual analysis shows how higher barriers to foreign bank entry alter the composition of international bank flows and may reverse the direction of net interbank flows. It also highlights that interbank lending and lending to non-banking firms respond differently to changes in foreign and domestic conditions. Ultimately, the analysis suggests that policies that change cross-border banking frictions and, thereby, the composition of banks’ foreign activities affect how shocks are transmitted across borders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The model provides a potential explanation for the patterns in Figure 1 but the chart should be seen as mainly motivational. The paper does not test in how far the model generates the observed patterns in the chart but instead uses German bank-level data to support the proposed theory.

In Bruno and Shin (2015), intrabank and interbank lending are isomorphic. In Niepmann (2015), interbank funding, cross-border deposit taking and borrowing from foreign affiliates are isomorphic. Niepmann (2013) abstracts from interbank lending. In de Blas and Russ (2013), cross-border lending and lending through foreign affiliates are considered as separate scenarios. Corbae and D’Erasmo (2010) study banking industry dynamics without allowing for interbank lending. Building on the aforementioned work, Corbae and D’Erasmo (2014) introduce interbank lending into a closed economy without considering foreign bank operations.

This in line with in the modeling approach in Boissay (2011), for example.

See de Haas and van Lelyveld (2010), Ongena, Peydro, and van Horen (2013), and de Haas and van Lelyveld (2014). Foreign bank ownership can also provide support in a domestic crisis as documented in Jeon, Olivero, and Wu (2013), Popov and Udell (2012), and de Haas and van Lelyveld (2006).

See Schnabl (2012), Reinhardt and Riddiough (2014), and McCauley, McGuire, and von Peter (2012). Additional work suggests that local lending by affiliates is more stable than cross-border lending by the parent banks. See Milesi-Ferretti and Tille (2011), Cetorelli and Goldberg (2011), de Haas and van Horen (2013), Kamil and Rai (2010), Duewel, Frey, and Lipponer (2011).

Cuts in the supply of credit by banks have been shown to have adverse effects on production and employment. See, for example, Khwaja and Mian (2008), Rosengren and Peek (2000), and Chodorow-Reich (2014).

For papers that introduce global banks in international macro, see, for example, Kollmann (2013), Olivero (2010), Kollmann, Enders, and Mueller (2011), and Greenwood, Sanchez, and Wang (2013).

The supply of domestic deposits is assumed to be fixed and the same for each bank. This assumption simplifies the model greatly because it eliminates any additional source of heterogeneity on the liability side of banks’ balance sheets. Interbank borrowing and lending is simply the gap between banks’ optimal loan volumes (which differ across banks) and deposits (which are the same for each bank) and is not an endogenous choice. To model the liability side of banks’ balance sheets more explicitly, one could assume, for example, that bankers compete for deposits, facing convex costs of raising deposits. The deposit rate would then be a function of the interbank lending rate and the cost of raising deposits. The size of domestic deposits on banks’ balance sheets would vary across banks. As we show later based on German bank-level data, the model predictions regarding banks’ net interbank lending and borrowing hold in the data. Thus, the model captures key features of banks’ funding composition even without more sophisticated modeling of the deposit side.

Heterogeneity in the cost of financial intermediation is also modeled in de Blas and Russ (2010) and de Blas and Russ (2013).

This could be rationalized as follows: As the size of a banker’s loan portfolio increases, the quality of the borrowers goes down, reflected in higher per unit monitoring costs. Alternatively, organizational complexity may increase with bank size and lead to higher operating costs.

It is assumed that parameters are such that investment and financial intermediation are beneficial in the economy so that all funds are in fact invested in projects. This requires that monitoring costs are not too high so that R−1/a′>1.

An alternative interpretation of our assumption is that banks want to invest at home and abroad in order to diversify. If risk is reduced, banks may be able to increase their leverage and, thereby, the size of their balance sheets. Love for variety in loans is modeled in de Blas and Russ (2010).

There is empirical evidence that information frictions and distance affect banks’ foreign activities. See Buch (2003), Focarelli and Pozzolo (2005) and Degryse and Ongena (2005).

The condition insures that the fixed cost of establishing an affiliate f ij F net of the benefits from raising deposits in country i (RId i ) is always larger than the fixed cost of cross-border lending.

An affiliate in our framework can be interpreted both as a branch and a subsidiary, although the interpretation as a subsidiary is preferred. Branches often facilitate lending to or borrowing from foreign banks or wholesale investors. In contrast, subsidiaries make it easier for banks to raise retail deposits in a foreign market. The model could distinguish between branch and subsidiary by assuming that a branch implies δ ij X=δ ij F whereas a subsidiary allows banks to compete for foreign deposits.

Note that φ bi is normalized separately for banks with cross-border lending and banks with affiliate lending.

Research Data and Service Centre of the Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Balance Sheet Statistics and External Positions of Banks, 2005.

The described grouping is based specifically on German banks’ positions vis-à-vis the nonbank private sector in country i.

For a discussion of the nonnegligible role of German banks’ third-country affiliates, see Frey and Kerl (2015).

These findings are consistent with Buch, Koch, and Koetter (2011) and Niepmann (2013) who show that bank efficiency predicts the intensive margin (and extensive margin) of banks’ foreign activities.

We use artificially constructed data in this graph as original bank-level data cannot be shown due to confidentiality.

The set of banks with local affiliate lending to country i is smaller than the set of banks with local and/or affiliate lending channelled from third countries to country i. φ bi is renormalized after banks are regrouped so that the mean of φ bi within each group is 1.

The three highest and lowest values of each dependent variable are excluded from the sample. This essentially means excluding countries in which only very few German banks operate, that is, countries for which the calculated values of δX, fX, δF and fF−RId are based on only a few observations.

See the data appendix for data sources and further details on the different variables.

The sufficient condition guarantees that a bank’s demand for interbank funds does not decline when it opens up an affiliate in a foreign country.

We exploit the fact that when a Pareto distribution is truncted, the resulting distribution is also Pareto distributed and has the same shape parameter.

Bremus and others (2013) find similar Pareto shape parameters for Germany and the United States.

Ideally, we would like to go back further in time. However, the large rise in BIS foreign claims took place after 1998 as indicated by Figure 1 so using 1998 values for autarky net interest margins seems sensible.

See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Systems, www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/releases/statisticsdata.htm, table H.8—Assets and Liabilities of Commercial Banks in the U.S., and the Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Report, www.bundesbank.de/Navigation/EN/Publications/Monthly_reports/monthly_reports.html, table IV.2 Banks—Principal Assets and Liabilities of Banks (MFIs) in Germany, by Category of Banks.

This is not an unreasonable assumption. According to the BIS statistics, the claims of German banks on the U.S. nonbank private sector in 2005 were roughly 20 times higher than the claims of U.S. banks on the German nonbank private sector.

Note that the lower limits of the German and U.S. bank efficiency distributions were set so that the model matches these values in autarky.

Similar to Figure 1, the share of German claims on U.S. banks relative to total German claims in the United States has fallen steadily since the late 1990s. The difference between German claims on U.S. banks and U.S. claims on German banks in the BIS data (a proxy for net interbank lending between Germany and the United States) became smaller over the period from 1999 to 2010, with the difference turning negative for the first time at the end of 2004. Based on the model, these patterns are consistent with a reduction of the barriers to German bank operations in the United States.

The model does not quantitatively match well the amount of U.S. deposits that German banks take because competition for deposits is not modeled in great detail. However, the model is useful for its qualitative implications regarding bank liabilities and funding composition.

In the chart, it is assumed that the affiliates of German banks do not raise funding on the interbank market from U.S. banks but that the funds to fill the gap between affiliate loans and deposits are provided by the parent.

Note that while the model pins down gross cross-border loans and gross local loans to U.S. nonbanking firms, only net interbank and intrabank flows are determined.

Bins do not contain exactly the same number of countries since we allocated all countries with the same level of openness to the same bin.

A similar pattern is also observed in the BIS data. The share of claims on banks compared with claims on the nonbank private sector held by BIS reporting countries is higher in less developed countries.

Empirical studies tend to compare the responses of different types of international bank flows to shocks without taking into account that these flows are determined simultaneously.

For references, see footnotes 5 and 6.

References

Aviat, Antonin and Nicolas Coeurdacier, March 2007, “The Geography of Trade in Goods and Asset Holdings,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 71, No. 1, pp. 22–51.

Beck, Thorsten, Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, and Ross Levine, 2000, “A New Database on the Structure and Development of the Financial Sector,” World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 597–605.

Boissay, Frederic, 2011, “Financial Imbalances and Financial Fragility,” Working Paper Series 1317 (European Central Bank).

Bremus, Franziska, Claudia Buch, Katheryn Russ, and Monika Schnitzer, 2013, “Big Banks and Macroeconomic Outcomes: Theory and Cross-Country Evidence of Granularity,” NBER Working Papers 19093 (National Bureau of Economic Research, May).

Bruno, Valentina and Hyun Song Shin, 2015, “Cross-Border Banking and Global Liquidity,” Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 82, No. 2, pp. 535–64.

Buch, Claudia M, 2003, “Information or Regulation: What Drives the International Activities of Commercial Banks,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 35, No. 6, pp. 851–69.

Buch, Claudia M., Catherine Tahmee Koch, and Michael Koetter, 2011, “Size, Productivity and International Banking,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 85, No. 2, pp. 329–34.

Cetorelli, Nicola and Linda S. Goldberg, 2011, “Global Banks and International Shock Transmission: Evidence from the Crisis,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 59, No. 1, pp. 41–76.

Chinn, Menzie and Hiro Ito, 2008, “A New Measure of Financial Openness,” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 309–322.

Chodorow-Reich, Gabriel, 2014, “The Employment Effects of Credit Market Disruptions: Firm-level Evidence from the 2008-09 Financial Crisis,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 129, No. 1, pp. 1–59.

Cihak, Martin, Asi Demirgüç-Kunt, Erik Feyen, and Ross Levine, 2012, “Benchmarking Financial Development Around the World,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 6175, pp. 1–58.

Corbae, Dean and Pablo D’Erasmo, 2010, “A Quantitative Model of Banking Industry Dynamics,” 2010 Meeting Papers 268 (Society for Economic Dynamics).

Corbae, Dean and Pablo D’Erasmo, 2014, “Capital Requirements in a Quantitative Model of Banking Industry Dynamics,” Working Papers 14-13 (Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia).

Craig, Ben R. and Goetz von Peter, 2014, “Interbank Tiering and Money Center Banks,” Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 322–47.

de Blas, Beatriz and Katheryn Niles Russ, 2010, “FDI in the Banking Sector,” NBER Working Papers 16029 (National Bureau of Economic Research).

de Blas, Beatriz and Katheryn Niles Russ, 2013, “All Banks Great, Small, and Global: Loan Pricing and Foreign Competition,” International Review of Economics & Finance, Vol. 26, No. C, pp. 4–24.

de Haas, Ralph and Iman van Lelyveld, July 2006, “Foreign Banks and Credit Stability in Central and Eastern Europe. A Panel Data Analysis,” Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 30, No. 7, pp. 1927–52.

de Haas, Ralph and Iman van Lelyveld, January 2010, “Internal Capital Markets and Lending by Multinational Bank Subsidiaries,” Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 1–25.

de Haas, Ralph and Iman van Lelyveld, 02 2014, “Multinational Banks and the Global Financial Crisis: Weathering the Perfect Storm?,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 46, No. s1, pp. 333–64.

de Haas, Ralph and Neeltje van Horen, 2013, “Running for the Exit? International Bank Lending During a Financial Crisis,” Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 244–85.

de Sousa, Jose, Thierry Mayer, and Soledad Zignago, 2012, “Market access in global and Regional Trade,” Regional Science and Urban Economics, Vol. 42, No. 6, pp. 1037–52.

Degryse, Hans and Steven Ongena, 2005, “Distance, Lending Relationships, and Competition,” The Journal of Finance, Vol. 60, No. 1, pp. 231–66.

Duewel, Cornelia, Rainer Frey, and Alexander Lipponer, 2011, “Cross-border bank lending, risk aversion and the financial crisis,” Discussion Paper Series 1: Economic Studies 2011,29 (Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Centre).

Focarelli, Dario and Alberto Franco Pozzolo, November 2005, “Where Do Banks Expand Abroad? An Empirical Analysis,” Journal of Business, Vol. 78, No. 6, pp. 2435–64.

Frey, Rainer and Cornelia Kerl, 2015, “Multinational Banks in the Crisis: Foreign Affiliate Lending as a Mirror of Funding Pressure and Competition on the Internal Capital Market,” Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 50, pp. 52–68.

Greenwood, Jeremy, Juan M. Sanchez, and Cheng Wang, 2013, “Quantifying the Impact of Financial Development on Economic Development,” Review of Economic Dynamics, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 194–215. Special issue: Misallocation and Productivity.

Head, Keith, Thierry Mayer, and John Ries, May 2010, “The Erosion of Colonial Trade Linkages after Independence,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 81, No. 1, pp. 1–14.

Janicki, Hubert and Edward Prescott, 2006, “Changes in the Size Distribution of U.S. Banks: 1960-2005,” Economic Quarterly, Vol. 92, No. 4, pp. 291–316.

Jeon, Bang Nam, Maria Pia Olivero, and Ji Wu, 2013, “Multinational Banking and the International Transmission of Financial Shocks: Evidence from Foreign Bank Subsidiaries,” Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 37, No. 3, pp. 952–72.

Kamil, Herman and Kulwant Rai, 2010, “The Global Credit Crunch and Foreign Banks’ Lending to Emerging Markets: Why Did Latin America Fare Better?” IMF Working Papers 10/102 (International Monetary Fund, April).

Khwaja, Asim Ijaz and Atif Rehman Mian, 2008, “Tracing the Impact of Bank Liquidity Shocks: Evidence from an Emerging Market,” American Economic Review, Vol. 98, No. 4, pp. 1413–42.

Kollmann, Robert, 2013, “Global Banks, Financial Shocks, and International Business Cycles: Evidence from an Estimated Model,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 45, No. s2, pp. 159–95.

Kollmann, Robert, Zeno Enders, and Gernot J. Mueller, 2011, “Global Banking and International Business Cycles,” European Economic Review, Vol. 55, No. 3, pp. 407–26. Special Issue: Advances in International Macroeconomics: Lessons from the Crisis.

McCauley, Robert, Patrick McGuire, and Goetz von Peter, 2012, “After the Global Financial Crisis: From International to Multinational Banking?,” Journal of Economics and Business, Vol. 64, No. 1, pp. 7–23.

Milesi-Ferretti, Gian-Maria and Cedric Tille, 04 2011, “The Great Retrenchment: International Capital Flows During the Global Financial Crisis,” Economic Policy, Vol. 26, No. 66, pp. 289–346.

Niepmann, Friederike, 2013, Banking Across Borders with Heterogeneous Banks, Staff Reports 609 (Federal Reserve Bank of New York).

Niepmann, Friederike, 2015, “Banking Across Borders,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 96, No. 2, pp. 244–65.

Olivero, Maria Pia, March 2010, “Market Power in Banking, Countercyclical Margins and the International Transmission of Business Cycles,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 80, No. 2, pp. 292–301.

Ongena, Steven, Jose Luis Peydro, and Neeltje van Horen, 2013, “Shocks Abroad, Pain at Home? Bank-Firm Level Evidence on the International Transmission of Financial Shocks,” DNB Working Papers 385 (Netherlands Central Bank, Research Department July).

Popov, Alexander and Gregory F. Udell, 2012, “Cross-Border Banking, Credit Access, and the Financial Crisis,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 87, No. 1, pp. 147–61.

Reinhardt, Dennis and Steven J. Riddiough, 2014, “The Two Faces of Cross-Border Banking Flows: An Investigation Into the Links Between Global Risk, Arms-Length Funding and Internal Capital Markets,” Working Paper 498 (Bank of England, April).

Rosengren, Eric S. and Joe Peek, 2000, “Collateral Damage: Effects of the Japanese Bank Crisis on Real Activity in the United States,” American Economic Review, Vol. 90, No. 1, pp. 30–45.

Schnabl, Philipp, 2012, “The International Transmission of Bank Liquidity Shocks: Evidence from an Emerging Market,” The Journal of Finance, Vol. 67, No. 3, pp. 897–932.

Stigum, Marcia, 1990, The Money Market (Dow Jones-Irwin: Homewood, IL).

Additional information

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Deutsche Bundesbank, their staff, or of any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System or the Deutsche Bundesbank

*Friederike Niepmann is an Economist in the International Finance Division at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Dr. Niepmann studied international economics at the University of Tübingen, Tufts University and the London School of Economics. She received her Ph.D. from the European University Institute in Florence in June 2012. Cornelia Kerl is an Economist in the Monetary Policy and Analysis Division of Deutsche Bundesbank. Dr. Kerl studied international economics at the University of Tübingen and the University of Paris I–Panthéon-Sorbonne. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Giessen in 2014. The authors thank Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Galina Hale, Katheryn Russ, Tim Schmidt-Eisenlohr, Vania Stavrakeva, Frederic Boissay, and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments. This paper was prepared for the DNB/IMF conference “International Banking: Microfoundations and Macroeonomic Implications.”

Firms refer to nonbanking firms as opposed to banks in this paper.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/s41308-017-0034-4.

Electronic supplementary material

Appendices

Appendix I

Data Appendix

Data from the Deutsche Bundesbank

The main data source for the empirical analysis in this paper are the External Positions Reports and Balance Sheet Statistics that German banks file with the Deutsche Bundesbank on a monthly basis. These reports contain information on the positions of parent banks, their branches and subsidiaries by country and sector. Bank-level data is confidential but available for research purposes on the premises of the Deutsche Bundesbank. All data used in this paper are for 2005. Our sample excludes foreign-owned banks but comprises all domestically owned banks with a German banking license. Banks fall into one of the following categories: commercial banks, Landesbanken, savings banks, regional institutions of credit cooperatives, credit cooperatives, building credit societies, savings and loan associations, and banks with special functions. We work with claims on the foreign nonbank private sector and claims on the foreign banking sector, excluding claims on foreign central banks. Claims represent accounts receivable and do not include securities holdings. When consolidating the parent bank and its affiliates, intragroup exposures are netted out by declaring liabilities that affiliates have on the German banking sector as representing parent bank funding.

Net Interest Margins

Information on net interest margins by country for 1998 and 2005 is from the World Bank’s Financial Development and Structure Dataset. Descriptions of this data set can be found in Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Levine (2000) and Cihak and others (2012). The net interest margin for the Netherlands Antilles is proxied by the value for Curaçao. The net interest margin for Serbia and Montenegro is the average between the net interest margins of the two countries.

Chinn-Ito Openness Index

Capital account openness is proxied by the Chinn & Ito Index documented in Chinn (2008). It is a de jure measure of openness, which increases with greater capital account openness of a country.

Bureaucratic Quality

Bureaucratic quality is from the International Country Risk Guide provided by the PRS Group.Footnote 40 A high value of the index means that obstacles to conduct business stemming from bureaucracy are low, as bureaucracy “has the strength and expertise to govern without drastic changes in policy or interruptions in government services.”

Property Rights Protection

Information on property rights protection comes from the Heritage Foundation.Footnote 41 The index increases with greater protection of private property by a country’s laws and the enforcement of those laws.

Other Country-Level Variables

GDP in current U.S. dollars is from the World Development Indicators. Distance from Germany to foreign countries comes from a data set provided by CEPII (see de Sousa, Mayer, and Zignago, 2012 and Head, Mayer, and Ries, 2010).

Appendix II

Proof of Proposition

Proof.

-

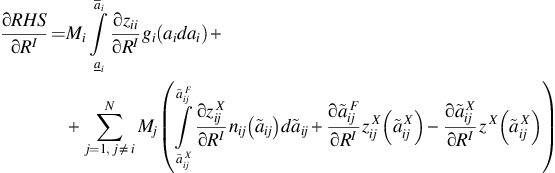

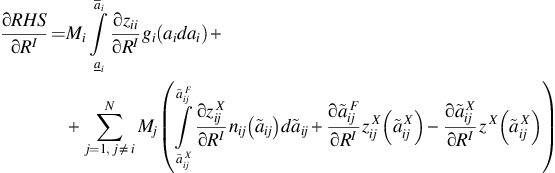

When RI=max{R1, R2 …, R N }, RHS of equation (17) is equal to zero. If RI=0, then RHS>∑i=1NK i because monitoring is assumed to be beneficial, which implies K i a′ i R i >K i . RHS of Equation (17) is strictly decreasing in RI on the interval RI∈[0, max{R1, R2 …, R N }]. To see this, note that:

because

because  Under the assumption that f

ij

F>f

ij

X−(K

i

)/(M

i

)max{R1, R2…, R

N

},

Under the assumption that f

ij

F>f

ij

X−(K

i

)/(M

i

)max{R1, R2…, R

N

},  This implies that (∂RHS)/(∂RI)<0. With RHS of equation (17) being strictly decreasing in RI, it follows that RHS of equation (17) cuts LHS of equation (17) once from above on the interval RI∈]0, max{R1, R2, …, R

N

}].

This implies that (∂RHS)/(∂RI)<0. With RHS of equation (17) being strictly decreasing in RI, it follows that RHS of equation (17) cuts LHS of equation (17) once from above on the interval RI∈]0, max{R1, R2, …, R

N

}].

because

because  Under the assumption that f

ij

F>f

ij

X−(K

i

)/(M

i

)max{R1, R2…, R

N

},

Under the assumption that f

ij

F>f

ij

X−(K

i

)/(M

i

)max{R1, R2…, R

N

},  This implies that (∂RHS)/(∂RI)<0. With RHS of

This implies that (∂RHS)/(∂RI)<0. With RHS of