Abstract

Jointly identifying brain diseases and predicting clinical scores have attracted increasing attention in the domain of computer-aided diagnosis using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data, since these two tasks are highly correlated. Although several joint learning models have been developed, most existing methods focus on using human-engineered features extracted from MRI data. Due to the possible heterogeneous property between human-engineered features and subsequent classification/regression models, those methods may lead to sub-optimal learning performance. In this paper, we propose a deep multi-task multi-channel learning (DM\(^2\)L) framework for simultaneous classification and regression for brain disease diagnosis, using MRI data and personal information (i.e., age, gender, and education level) of subjects. Specifically, we first identify discriminative anatomical landmarks from MR images in a data-driven manner, and then extract multiple image patches around these detected landmarks. A deep multi-task multi-channel convolutional neural network is then developed for joint disease classification and clinical score regression. We train our model on a large multi-center cohort (i.e., ADNI-1) and test it on an independent cohort (i.e., ADNI-2). Experimental results demonstrate that DM\(^2\)L is superior to the state-of-the-art approaches in brain diasease diagnosis.

M. Liu and J. Zhang—These authors contribute equally to this paper.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

For the challenging and interesting task of computer-aided diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and its prodromal stage (i.e., mild cognitive impairment, MCI), brain morphometric pattern analysis has been widely investigated to identify disease-related imaging biomarkers from structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [1,2,3]. Compared with other widely used biomarkers (e.g., cerebrospinal fluid), MRI provides a non-invasive solution to potentially identify abnormal structural brain changes in a more sensitive manner [4, 5]. While extensive MRI-based studies focus on predicting categorical variables in binary classification tasks, the multi-class classification task remains a challenging problem. Moreover, several pattern regression methods have been developed to estimate continuous clinical scores using MRI [6]. This line of research is very important since it can help evaluate the stage of AD/MCI pathology and predict its future progression. Different from the classification task that categorizes an MRI into binary or multiple classes, the regression task needs to estimate continuous values, which is more challenging in practice.

Actually, the tasks of disease classification and clinical score regression may be highly associated, since they aim to predict semantically similar targets. Hence, jointly learning these two tasks can utilize the intrinsic useful correlation information among categorical and clinical variables to promote the learning performance [6]. Existing methods generally first extract human-engineered features from MR images, and then feed these features into subsequent classification/regression models. Due to the possibly heterogeneous property between features and models, these methods usually lead to sub-optimal performance because of simply utilizing the limited human-engineered features. Intuitively, integrating the feature extraction and the learning of models into a unified framework could improve the diagnostic performance. Also, personal information (e.g., age, gender, and education level) may also be related to brain status, and thus can affect the diagnostic performance for AD/MCI. However, it is often not accurate to simultaneously match multiple parameters for different clinical groups.

In this paper, we propose a deep multi-task multi-channel learning (DM\(^2\)L) framework for joint classification and regression of brain status using MRI. Compared with conventional methods, DM\(^2\)L can not only automatically learn representations for MRI without requiring any expert knowledge for pre-defining features, but also explicitly embed personal information (i.e., age, gender, and education level) into the learning model. Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of DM\(^2\)L. We first process MR images and identify anatomical landmarks in a data-driven manner, followed by a patch extraction procedure. We then propose a multi-task multi-channel convolutional neural network (CNN) to simultaneously perform multi-class disease classification and clinical score regression.

2 Materials and Methods

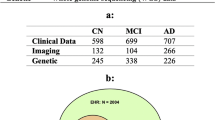

Data Description: Two public datasets containing 1396 subjects are used in this study, including Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative-1 (ADNI-1) [7], and ADNI-2 [7]. For independent testing, subjects participated in both ADNI-1 and ADNI-2 are simply removed from ADNI-2. Subjects in the baseline ADNI-1 dataset have 1.5T T1-weighted MRI data, while subjects in the baseline ADNI-2 dataset have 3T T1-weighted MRI data. More specifically, ADNI-1 contains 226 normal control (NC), 225 stable MCI (sMCI), 165 progressive MCI (pMCI), and 181 AD subjects. In ADNI-2, there are 185 NC, 234 sMCI, 37 pMCI, and 143 AD subjects. Both sMCI and pMCI are defined based on whether MCI subjects would convert to AD within 36 months after the baseline time. Four types of clinical scores are acquired for each subject in both ADNI-1 and ADNI-2, including Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDRSB), classic Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale Cognitive (ADAS-Cog) subscale with 11 items (ADAS11), modified ADAS-Cog with 13 items (ADAS13), and Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE). We process all studied MR images via a standard pipeline, including anterior commissure (AC)-posterior commissure (PC) correction, intensity correction, skull stripping, and cerebellum removing.

Illustration of (left) all identified AD-related anatomical landmarks, and (right) \(L=50\) selected landmarks with colors denoting p-values in group comparison [8].

Data-Driven Anatomical Landmark Identification: To extract informative patches from MRI for both feature learning and model training, we first identify discriminative AD-related landmark locations using a data-driven landmark discovery algorithm [8, 9]. The aim is to identify the landmarks that have statistically significant group difference between AD patients and NC subjects in local brain structures. More specifically, using the Colin27 template, both linear and non-linear registration are performed to establish correspondences among voxels in different MR images. Then, morphological features are extracted from local image patches around the corresponding voxels in the linearly-aligned AD and NC subjects from ADNI-1. A voxel-wise group comparison between AD and NC groups is then performed in the template space, through which a p-value can be calculated for each voxel. In this way, a p-value map can be obtained, whose local minima are defined as locations of discriminative landmarks in the template. In Fig. 2(left), we illustrate the identified anatomical landmarks based on AD and NC subjects in ADNI-1. For a new testing MR image, one can first linearly align it to the template space, and then use a pre-trained landmark detector to localize each landmark. In this study, we assume that landmarks with significant differences between AD and NC groups are potential atrophy locations of MCI subjects. Accordingly, all pMCI and sMCI subjects share the same landmarks as those identified from AD and NC groups.

Patch Extraction from MRI: Based on the identified landmarks, we extract image patches from an MR image of a specific subject. As shown in Fig. 2(left), some landmarks are close to each other. In such a case, patches extracted from these landmark locations will have large overlaps, and thus can only provide limited information about the structures of MR images due to redundant information. To this end, we define a spatial distance threshold (i.e., 20 voxels) to control the distance of landmarks, in order to reduce the overlaps of patches. In Fig. 2(right), we plot the \(L=50\) selected landmarks, from which we can see that many of these selected landmarks are located in the areas of bilateral hippocampal, parahippocampal, and fusiform. These areas are reported to be related to AD/MCI in previous studies [10, 11]. Then, for each subject, we can extract L image patches (with the size of \(24 \times 24 \times 24\)) based on L landmarks, and each patch center is a specific landmark location. We further randomly extract image patches centered at each landmark location with displacements in a \(5\times 5\times 5\) cubic, in order to reduce the impact of landmark detection errors.

Multi-Task Multi-Channel CNN: As shown in Fig. 3, we propose a multi-task multi-channel CNN, which allows the learning model to extract feature representations implicitly from the input MRI patches. This architecture adopts multi-channel input data, where each channel is corresponding to a local image patch extracted from a specific landmark location. In addition, we incorporate personal information (i.e., age, gender, and education level) into the learning model, in order to investigate the impact of personal information on the performance of computer-aided disease diagnosis. As shown in Fig. 3, the input of this network includes L image patches, age, gender, and education level from each subject, while the output contains the class labels and four clinical scores (i.e., CDRSB, ADAS11, ADAS13, and MMSE). Since the appearance of brain MRI is often globally similar and locally different, both global and local structural information could be important for the tasks of classification and regression. To capture the local structural information of MRI, we first develop L-channel parallel CNN architectures. In each channel CNN, there is a sequence of six convolutional layers and two fully connected (FC) layers (i.e., FC7, and FC8). Each convolution layer is followed by a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function, while Conv2, Conv4, and Conv6 are followed by \(2\times 2\times 2\) max-pooling operations for down-sampling. Note that each channel contains the same number of convolutional layers and the same parameters, while their weights are independently optimized and updated. To model the global structural information of MRI, we then concatenate the outputs of L FC8 layers, and add two additional FC layers (i.e., FC9, and FC10) to capture the global structural information of MRI. Moreover, we feed a concatenated representation comprising the output of FC10 and personal information (i.e., age, gender, and education level) into two FC layers (i.e., FC11, and FC12). Finally, two FC13 layers are used to predict the class probability (via soft-max) and to estimate the clinical scores, respectively. The proposed network can also be mathematically described as follows.

Let \(\mathcal {X}=\{\mathbf{X}_n\}_{n=1}^{N}\) denote the training set, with the element \(\mathbf{X}_n\) representing the n-th subject. Denote the labels of C (\(C=4\)) categories as \(\mathbf{y}^c=\{y^c_n\}_{n=1}^{N} \left( c=1,2,\cdots ,C \right) \), and S (\(S=4\)) types of clinical scores as \(\mathbf{z}^s=\{z^s_n\}_{n=1}^{N} \left( s=1,2,\cdots ,S \right) \). In this study, both the class labels and clinical scores are used in a back-propagation procedure to update the network weights in the convolutional layers and to learn the most relevant features in the FC layers. The aim of the proposed CNN is to learn a non-linear mapping \(\varPsi : \mathcal {X} \rightarrow \left( \left\{ {\mathbf{y}^c}\right\} _{c=1}^{C},\left\{ {\mathbf{z}^s }\right\} _{s=1}^{S} \right) \) from the input space to both spaces of the class label and the clinical score, and the objective function is as follows:

where the first term is the cross-entropy loss for multi-class classification, and the second one is the mean squared loss for regression to evaluate the difference between the estimated clinical score \(\widetilde{z}_n^s\) and the ground truth \(z_n^s\). Note that \(1 \left\{ {\cdot } \right\} \) is an indicator function, with \(1 \left\{ {\cdot }\right\} =1\) if \( \left\{ {\cdot }\right\} \) is true; and 0, otherwise. In addition, \(\mathbf{P}(y^c_n=c | \mathbf{X}_n;\mathbf{W})\) indicates the probability of the subject \(\mathbf{X}_n\) being correctly classified as the category \(y^c_n\) using the network coefficients \(\mathbf{W}\).

3 Experiments

Experimental Settings: We perform both multi-class classification (NC vs. sMCI vs. pMCI vs. AD) and regression of four clinical scores (CDRSB, ADAS11, ADAS13, and MMSE). The performance of multi-class classification is evaluated by the overall classification accuracy (Acc) for four categories, as well as the accuracy for each category. The performance of regression is evaluated by the correlation coefficient (CC), and the root mean square error (RMSE). To evaluate the generalization ability and the robustness of a specific model, we adopt ADNI-1 as the training dataset, and ADNI-2 as the independent testing dataset.

We compare our DM\(^2\)L method with two state-of-the-art methods, including (1) voxel-based morphometry (VBM) [12], and (2) ROI-based method (ROI). In the VBM, we first normalize all MR images to the anatomical automatic labeling (AAL) template using a non-linear image registration technique, and then extract the local GM tissue density in a voxel-wise manner as features. We also perform t-test to select informative features, followed by a linear support vector machine (LSVM) or a linear support vector regressor (LSVR) for classification or regression. In the ROI, the brain MRI is first segmented into three tissue types, i.e., gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). We then align the AAL template with 90 pre-defined ROIs to the native space of each subject using a deformable registration algorithm. Then, the normalized volumes of GM tissue in 90 ROIs are used as the representation of an MR image, followed by an LSVM or an LSVR for classification or regression.

To evaluate the contributions of the proposed two strategies (i.e., joint learning, and using personal information) adopted in DM\(^2\)L, we further compare DM\(^2\)L with its three variants. These variants include (1) deep single-task multi-channel learning (DSML) using personal information, (2) deep single-task multi-channel learning without using personal information (denoted as DSML-1), and (3) deep multi-task multi-channel learning without using personal information (denoted as DM\(^2\)L-1). Note that DSML-1 and DSML employ the similar CNN architecture as shown in Fig. 3, but perform the tasks of classification and regression separately. In addition, DM\(^2\)L-1 does not adopt any personal information for the joint learning of classification and regression. The size of image patch is empirically set to \(24\times 24\times 24\) in DM\(^2\)L and its three variants, and they share the same \(L=50\) landmarks as shown in Fig. 2(right).

Results: In Table 1, we report the experimental results achieved by six methods in the tasks of multi-class disease classification (i.e., NC vs. sMCI vs. pMCI vs. AD) and regression of four clinical scores. The confusion matrices for multi-class classification are given in the Supplementary Materials. Figure 4 further shows the scatter plots of the estimated scores vs. the true scores achieved by six different methods for four clinical scores, respectively. Note that the clinical scores are normalized to [0, 1] in the procedure of model learning, and we transform those estimated scores back to their original ranges in Fig. 4.

From Table 1 and Fig. 4, we can make at least four observations. First, compared with conventional methods (i.e., VBM, and ROI), the proposed 4 deep learning based approaches generally yield better results in both disease classification and clinical score regression. For instance, in terms of the overall accuracy, DM\(^2\)L achieves an \(11.4\%\) and an \(8.7\%\) improvement compared with VBM and ROI, respectively. In addition, VBM and ROI can only achieve very low classification accuracies (i.e., 0.081 and 0.027, respectively) for the pMCI subjects, while our deep learning based methods can achieve much higher accuracies. This implies that the integration of feature extraction into model learning provides a good solution for improving diagnostic performance, since feature learning and model training can be optimally coordinated. Second, in both classification and regression tasks, the proposed joint learning models are usually superior to the models that learn different tasks separately. That is, DM\(^2\)L usually achieves better results than DSML, and DM\(^2\)L-1 outperforms DSML-1. Third, DM\(^2\)L and DSML generally outperforms their counterparts (i.e., DM\(^2\)L-1, and DSML-1) that do not incorporate personal information (i.e., age, gender, and education level) into the learning process. It suggests that personal information helps improve the learning performance of the proposed method. Finally, as can be seen from Fig. 4, our DM\(^2\)L method generally outperforms those five competing methods in the regression of four clinical scores. Considering different signal-to-noise ratios of MRI in the training set (i.e., ADNI-1 with 1.5T scanners) and MRI in the testing set (i.e., ADNI-2 with 3T scanners), these results imply that the learned model via our DM\(^2\)L framework has good generalization capability.

4 Conclusion

We propose a deep multi-task multi-channel learning (DM\(^2\)L) framework for joint classification and regression of brain status using MRI and personal information. Results on two public cohorts demonstrate the effectiveness of DM\(^2\)L in both multi-class disease classification and clinical score regression. However, due to the differences in data distribution between ADNI-1 and ADNI-2, it may degrade the performance to directly apply the model trained on ADNI-1 to ADNI-2. It is interesting to study a model adaptation strategy to reduce the negative influence of data distribution differences. Besides, studying how to automatically extract informative patches from MRI is meaningful, which will also be our future work.

References

Fox, N., Warrington, E., Freeborough, P., Hartikainen, P., Kennedy, A., Stevens, J., Rossor, M.N.: Presymptomatic hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 119(6), 2001–2007 (1996)

Liu, M., Zhang, D., Shen, D.: View-centralized multi-atlas classification for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36(5), 1847–1865 (2015)

Liu, M., Zhang, J., Yap, P.T., Shen, D.: View-aligned hypergraph learning for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis with incomplete multi-modality data. Med. Image Anal. 36, 123–134 (2017)

Frisoni, G.B., Fox, N.C., Jack, C.R., Scheltens, P., Thompson, P.M.: The clinical use of structural MRI in Alzheimer disease. Nature Rev. Neurol. 6(2), 67–77 (2010)

Liu, M., Zhang, D., Shen, D.: Relationship induced multi-template learning for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 35(6), 1463–1474 (2016)

Sabuncu, M.R., Konukoglu, E., Initiative, A.D.N., et al.: Clinical prediction from structural brain MRI scans: A large-scale empirical study. Neuroinformatics 13(1), 31–46 (2015)

Jack, C.R., Bernstein, M.A., Fox, N.C., Thompson, P., Alexander, G., Harvey, D., Borowski, B., Britson, P.J., L Whitwell, J., Ward, C.: The Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI): MRI methods. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 27(4), 685–691 (2008)

Zhang, J., Gao, Y., Gao, Y., Munsell, B., Shen, D.: Detecting anatomical landmarks for fast Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 35(12), 2524–2533 (2016)

Zhang, J., Liu, M., An, L., Gao, Y., Shen, D.: Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis using landmark-based features from longitudinal structural MR images. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. (2017). doi:10.1109/JBHI.2017.2704614

De Jong, L., Van der Hiele, K., Veer, I., Houwing, J., Westendorp, R., Bollen, E., De Bruin, P., Middelkoop, H., Van Buchem, M., Van Der Grond, J.: Strongly reduced volumes of putamen and thalamus in Alzheimer’s disease: an MRI study. Brain 131(12), 3277–3285 (2008)

Hyman, B.T., Van Hoesen, G.W., Damasio, A.R., Barnes, C.L.: Alzheimer’s disease: cell-specific pathology isolates the hippocampal formation. Science 225, 1168–1171 (1984)

Baron, J., Chetelat, G., Desgranges, B., Perchey, G., Landeau, B., De La Sayette, V., Eustache, F.: In vivo mapping of gray matter loss with voxel-based morphometry in mild Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage 14(2), 298–309 (2001)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

1 Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Liu, M., Zhang, J., Adeli, E., Shen, D. (2017). Deep Multi-task Multi-channel Learning for Joint Classification and Regression of Brain Status. In: Descoteaux, M., Maier-Hein, L., Franz, A., Jannin, P., Collins, D., Duchesne, S. (eds) Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention − MICCAI 2017. MICCAI 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10435. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66179-7_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66179-7_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-66178-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-66179-7

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)